The Weekly Insight Podcast – Fear at the Fed

We wrote a memo a few years ago (you can read it here) where we discussed a weird phenomenon of our times. We were discussing the jobs report and its impact on Fed policy and the theory was this: bad jobs data (i.e., creating fewer jobs) was good for Fed policy and the market. Inversely, a good jobs report was bad for the market. It was a bit of an upside-down argument – good news bad/bad news good.

That’s been true for much of the last two years as the Fed has tried to fight inflation. The more the economy slowed down, the less restrictive the Fed would eventually be.

So that brings us to today. We got some incredibly good news about the economy last week (more on that in a minute) and there is a Fed meeting coming up this week. Will that good news make the Fed less likely to ring the rate cut bell? Let’s take a look.

GDP Surprises to the Upside

The never-ending misses by economists on GDP continued this week…in a big way. On Thursday we got the final GDP data for 2023 and it showed tremendously good news. GDP grew in Q4 by 3.3% and for the full year by 2.5%. That’s a strong improvement from the 1.9% growth we saw in 2022.

The “Wall Street Consensus”, even last week, held that GDP in Q4 would grow by 2%. If you go all the way back to the beginning of the year, the “consensus” was that we would have almost no gain for the full year. To put this in perspective, year-over-year GDP growth is nearly 12% higher than the 25-year average of 2.236%. 2023 was a good year.

Past performance is not indicative of future results.

Inflation Surprises to the Downside

All this economic growth must make it harder for inflation to meet the Fed’s targets, right? Not so much.

We’ve talked at length about the various measures of inflation before – but it’s important to remember that the Fed’s “preferred measure of inflation” is Personal Consumption Expenditures (PCE). More specifically, they really focus on Core PCE (PCE net of food and energy).

The day after we got the GDP data, we got the Core PCE data. Core PCE grew 0.2% month over month and 2.9% year-over-year. While that is still higher than the Fed’s 2% target, what happens if we look at its rate quarter-over-quarter? You’ll see from the chart below that it has been right at the Fed’s pace of 2% for the last six months. We’ve met the Fed’s target – we just haven’t done it for a full year.

Past performance is not indicative of future results.

So, What Does That Mean for the Fed?

This puts us in a bit of a good news/good news position. The economy is chugging right along all while inflation is meeting the Fed’s goals. So, does that mean rate cuts are imminent?

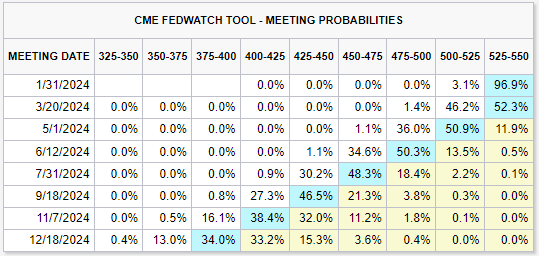

First, let’s get to the market’s expectations because they are changing. In our memo two weeks ago (What If the Consensus is Wrong?), we noted that the market was placing 76.4% odds on the first rate cut happening in March and expected the Fed to cut rates seven times in 2024. Today there is a less than 50% expectation that rate cuts will start in March (vs. 88.1% odds for the May meeting) and the market is pricing in six rate cuts in 2024.

Source: CMEGroup.com

Past performance is (obviously!) not indicative of future results.

So, all this good news has the market less optimistic on rate cuts. Why? Fear. And not fear in the market. But fear at the Fed.

What is the Fed afraid of? The 1970’s. As Martin Sandbu of the Financial Times stated in his column “Lies, Damned Lies, and Year-On-Year Inflation Rates”:

“The honest thing to say – if you really want to keep interest rates high – would be that the job is done but could come undone, so it’s better to keep rates high out of an abundance of caution”.

The point here, as Bloomberg columnist John Authers pointed out in Friday’s edition of “Points of Return” is that the Fed fears recreating the “worst central banking experience in modern history”: the Arthur Burns rate hikes – and cuts…and hikes – of the 1970s.

The Burns Fed thought it had rates under control by 1976 and started to cut rates – only to see inflation spike much higher (to nearly 15% by 1980). Their unwillingness to stand pat on rates caused even greater harm.

But this isn’t the 1970s. Our inflation problem was not caused by the systemic issues of going off the gold standard. Instead, it was caused by a worldwide pandemic that has been resolved. And our economy today is much more stable and much more improved relative to what we saw in the mid-1970s.

But that doesn’t mean mankind’s oldest emotion – fear – can’t rule the day at the Fed. They have an amygdala just like investors. And their greatest fear is being remembered in the same breath as the much-reviled Burns’ Fed. They’d rather be Paul Volcker, the great defeater of inflation.

They’ve said as much. Fed Governor Christopher Waller said earlier this month that “the worst thing we could have is if it (inflation) all reverses, and we have already cut”. Raphael Bostic, President of the Atlanta Fed said “I’m expecting it’s going to be bumpy and because of that bumpiness I feel like we’ve got to be careful. We do not want to go on these up and down or a back-and-forth pattern. I want us to be absolutely certain that inflation is where we need it to be before we move too dramatically”.

We’d argue they have it wrong. The “worst thing” isn’t having to raise rates again. The “worst thing” is being too restrictive on rates and driving us into an unnecessary recession.

So, what will Chairman Powell and his crew say this week? We’ll have to wait until Wednesday to find out. But the risk of an over-cautious approach may inject some volatility into the markets in the coming days and weeks.

Everyone keeps talking about a “soft landing”. The runway lights are on. Powell has been cleared for landing. But it won’t be good if he keeps going around and around until the plane runs out of gas. Let’s hope that’s not the message on Wednesday.

Sincerely,