Supply chain, supply chain. Turn on the news today and you can’t go five minutes without hearing about it in some way, shape, or form. But, too often, the stories are about the impending doom of the supply chain, without explaining the what, why, and how of the situation. We’d like to do that here today. We may not solve the problem in these pages – but we at least hope you’ll have a little better understanding of what’s going on and whether or not we should be ready for that “impending doom”.

Quick side note: there is a big piece of the supply chain that we’re not going to talk about today – labor. We’ve already covered that topic here. We would note an excellent article forwarded to us by a client which addresses labor economist Daniel Alpert’s take on the “Great Resignation”. He thinks it’s coming to an end soon. If that’s true, it just helps the supply chain issues we’re going to discuss today. You can read that article by clicking here.

How Did We Get Here?

Before we dig into where this goes next, we need to address how we got here in the first place. In our opinion it ties back to two fundamental things the economy has done:

- Just-In-Time Supply Chain Management

- COVID Overreaction

Ironically, both issues are best addressed by looking at the automobile industry (which is the source of much angst today).

Just-In-Time (JIT) manufacturing was – as the story goes – invented by the CEO of Toyota, Eiji Toyoda, in the 1950s. He visited United States auto manufacturers and saw significant waste in the production process. He saw an opportunity to innovate and dove right in. Toyota began to only order spare parts when needed and forced his suppliers to adjust to be able to provide a reliable stream when called on.

As you well know that process has spread across all areas of the economy since then. Toyoda’s process cut manufacturing costs, the costs to carry inventory, and the time it took to manufacture a product. Today it is used in cars, phones, clothes, you name it. The world shifted to “JIT”.

Then came COVID. Manufacturers had to make some decisions – especially in the automobile industry. How many cars would people buy during the pandemic? How quickly would the economy recover? They had to make some decisions so they could make their JIT orders.

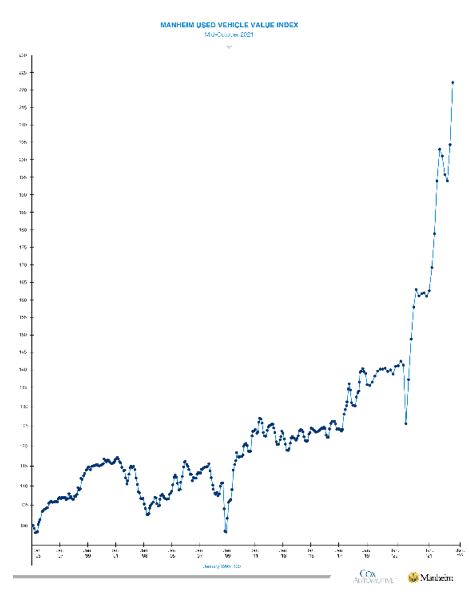

The story we have all been hearing about the auto industry is that they “can’t get” the semiconductors needed to build cars. That’s not really the whole story. Because, as the pandemic was getting underway, they made a decision: cut back on orders for semiconductors. Why? They did NOT predict the cash flowing into the pockets of citizens around the world. They thought, instead, that the demand for automobiles would go down (which it did, briefly). They just had no way of knowing just how quickly it would recover.

And so the makers of those semi-conductors had to make decisions as well. They shifted their manufacturing to other customers or cut back on production. So, by the time the auto industry figured out what was going on, they had already built a JIT supply shortage.

Where Do We Go Next: The Charmin Solution

This type of disruption has happened across the supply chain – but it hasn’t always been caused by the manufacturer’s incorrect assumptions about economic growth. Remember toilet paper? Yeah – we all went crazy for that stuff at the start of the pandemic!

Pre-COVID the toilet paper industry had its own version of “Just In Time” (there’s a joke here…but we’ll leave that to someone else!). They traditionally kept a 2-week inventory and did that with their plants running at 92 percent. Then came the COVID panic buying. They had a choice: work through the issue, or build massive new – and very expensive – facilities. They chose the former. They adjusted by bumping production all the way up to 100 percent. They also changed their product mix. They started making more “big roll” products which they could do more efficiently.

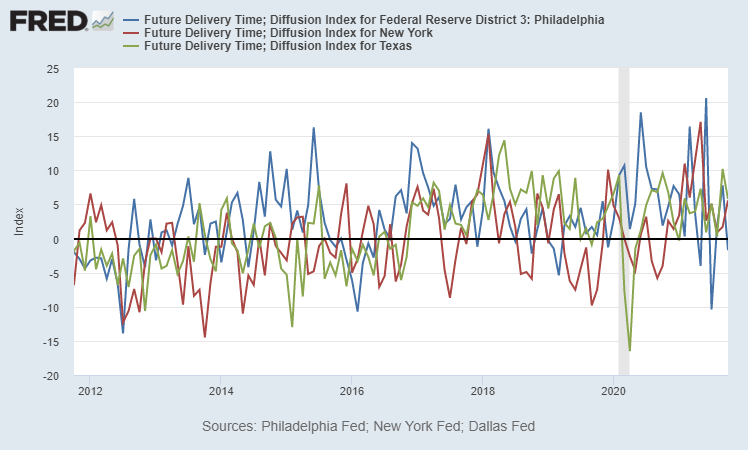

It was scary for a bit – but we all go through it. The rest of the supply chain is doing that as we speak. Inventories are well down from their peak, but they are improving and have been doing so since April. And while the data on “Current Delivery Times” looks a bit scary, manufacturers expectations for six-months from now are very much in keeping with the long-term historical trend.

This data set looks messy, but there is a clear peak in delivery times that ran from the beginning of this year through mid-summer. Since then, the natural order is starting to return. If manufacturers expectations are correct, this may be a very good sign.

One final point on this. We got the Q3 GDP numbers this week. They were drastically below the expectation at the beginning of the quarter, coming in at just 2% (vs. a 6% expectation three months ago). The reason for this – no doubt – was the Delta variant. People spent less money in the quarter as they were concerned about the impact of the resurgent virus.

But we would also argue this gave the supply chain a much needed breather. It allowed manufacturers an opportunity to catch up a bit (see the chart above) and may end up being the break needed to help surmount the supply chain issues we’re facing.

We have always been obstinately confident in the free market. That doesn’t come without a few bruises. The examples above about the failures of the supply chain to account for a catastrophic moment like a pandemic should certainly give pause. But it’s clear the market is figuring this one out. It’s going to take time. And it isn’t always going to be pretty. But we’re getting there.

Supply Chain Opportunities: Energy

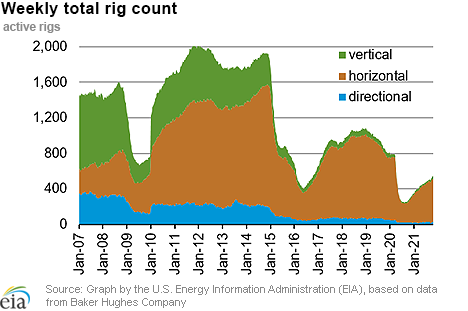

Since we love the free market so much, we might as well try to make a little money off all this disruption, right? There’s no place better to do that today, in our opinion, than the energy markets. Why? As prices are rising, the impact of COVID, governmental policy, and a tightening debt market mean energy producers just don’t have the ability – or the desire – to raise production.

Take the chart below as an example. Prior to COVID, the U.S. had roughly 800 oil and gas rigs operating domestically. That number was already down substantially from the 2019 count of more than 1,000 rigs. Today? There are just 542 rigs operating.

The old saying was “the cure for high energy prices was high energy prices”. Why? When prices got to these levels, everyone and their cousin started poking holes in the dirt. The added production eventually flooded the market and prices cratered. That may eventually be true, but it’s not happening now. It takes a long time for a well to bring production online. Even if everyone started drilling today, we wouldn’t see that impact for many months. And they’re not rushing to do so.

Instead, energy producers are looking to live in a new dynamic: cut costs, pay down debt, and pay a strong dividend. That means less production. Take our old friend Birchcliff Energy as an example: they just drilled enough wells to keep their production flat this year. They never intended to grow production. All in a time when natural gas prices have risen nearly 120%. That is starkly different from the energy market of the past.

We’ll leave it there for this week. Just another friendly reminder that the deadline for guaranteed execution on end of year paperwork at TD Ameritrade is November 15th – two weeks from today. If you have some end of year plans that need addressing, please touch base with your advisor soon!

Sincerely,