The Weekly Insight Podcast – Fed Certainty

It’s Fed week. Another interest rate decision looms. Much mashing of teeth will ensue on Wall Street as Chairman Powell steps to the podium to speak Wednesday afternoon at 1:30PM CDT. None of that is new for regular readers of the Weekly Insight!

It was a few years ago – just before another Fed meeting – that a question came up during a meeting of our Investment Committee:

“What would happen if the Fed surprised the world and did the opposite of what the market’s ‘consensus expectations’ were?

We started digging. And we learned something telling: barring times of crisis, the market consensus is almost always correct when the odds or a rate decision are above 80%. The market has been nearly spot-on regarding the “direction” of rates (raise, cut, or hold). Where some variation exists is the size of the decision (i.e., 0.25% or 0.50%).

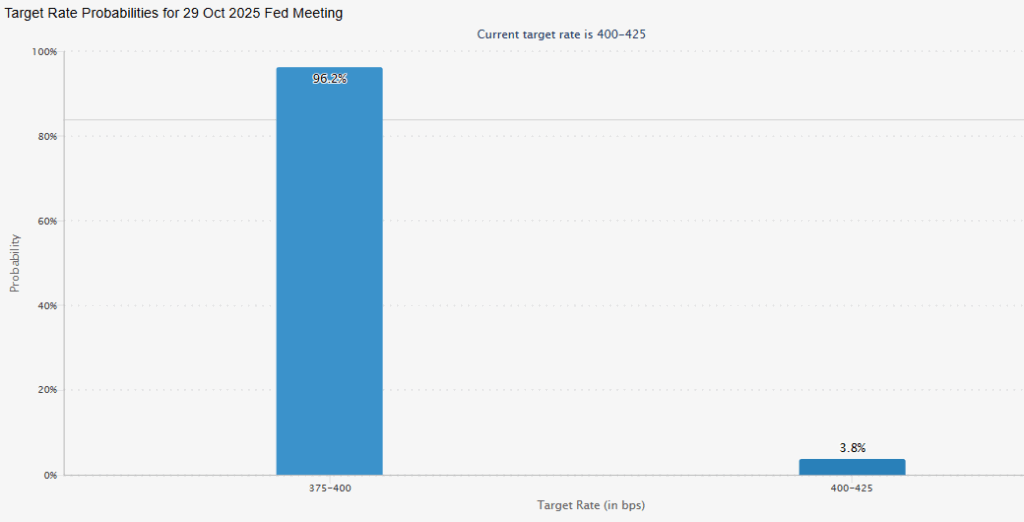

And so – given the chart below – it is safe to say we’ll see a rate cut on Wednesday. The size? That’s statistically to be determined. But we would be shocked if it were larger than 0.25%.

Source: CME Group

Past performance is not indicative of future results.

So why are Fed meetings so impactful on markets in the short term? If everyone knows what Powell is going to say, shouldn’t it just be another ho-hum day on Wall Street?

It’s not that easy. Because, as good as the market is at homing in on a short-term decision, it is horrible at solving the equation beyond the next meeting.

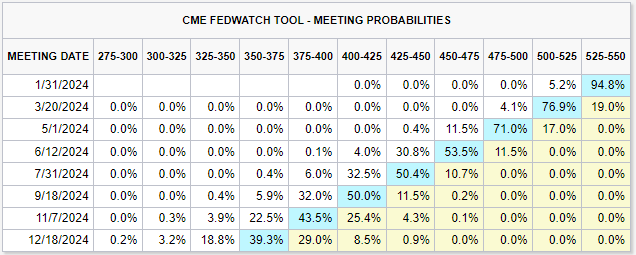

Take, for example, this chart we pulled from our January 15, 2024, Weekly Insight Memo titled What if the Consensus is Wrong? (hint: it was!). At the time the market predicted the following:

- No rate cut at the next meeting.

- Rate cuts beginning at the following meeting.

- Rates being cut in every remaining meeting for 2024 with rates to end the year at 3.50 – 3.75%.

Source: CME Group

Past performance is not indicative of future results.

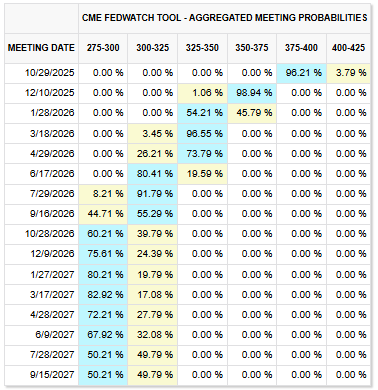

Yeah…that didn’t happen. Rate cuts didn’t start until September of 2024 and today we are finally at the point the market anticipated we would reach over a year ago. So, when we see the market’s future guidance showing 100% certainty of another rate cut in December and rates falling to 3% by late next year, we lack the confidence to embrace that prediction.

Source: CME Group

Past performance is not indicative of future results.

So, the question right now for investors is this: why might the market be wrong about future rate cuts? And is that particularly devastating to the market and/or the economy? Let’s take a look.

The Jobs Economy

As we’ve discussed many times, the Fed has two jobs: keeping employment up and inflation down. Yet they only have one tool to use: interest rates. Cutting rates helps jobs but makes inflation more likely. Keeping rates the same (or raising them) does the opposite.

And so, the most compelling argument for the market being correct on rate cuts is the risk the job market is weakening. But is it, really?

There are a few ways to answer this question. But first, let’s be blunt: no one knows. With the current government shutdown, the amount of data available on jobs is significantly less than we normally have. And it’s unlikely we’ll have an October employment report. Normally, we get weekly data. Now, the best we have is the monthly ADP figures which we won’t see until November 5th.

The last data we have – from September – was not strong. But it wasn’t problematic. We weren’t creating many jobs, but we weren’t losing them either. Unemployment was stable at 4.3%.

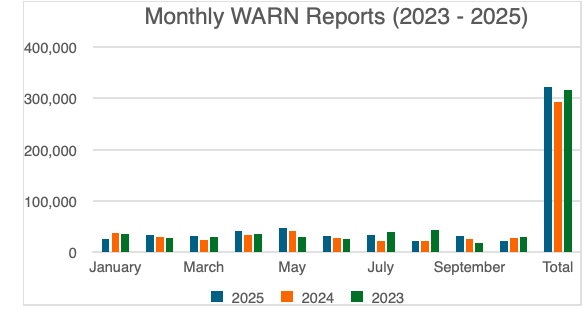

The question we need to answer is whether or not we’re going to see substantive job losses in coming months. And, thankfully, there’s a particularly good data set for this. When companies make decisions to cut jobs, they’re required to submit layoff data to the Worker Adjustment and Retraining Notification (WARN) database. And that data is publicly available and trackable by company, industry, and location. We pulled the data for the first ten months of the year and compared it with the previous two years. It can best be described as unremarkable. We’re slightly higher than the last two years, but there has been no significant influx of layoffs.

Source: WARN Database

Past performance is not indicative of future results.

All things being equal, there is not an employment crisis the Fed needs to fix with rate cuts.

Inflation

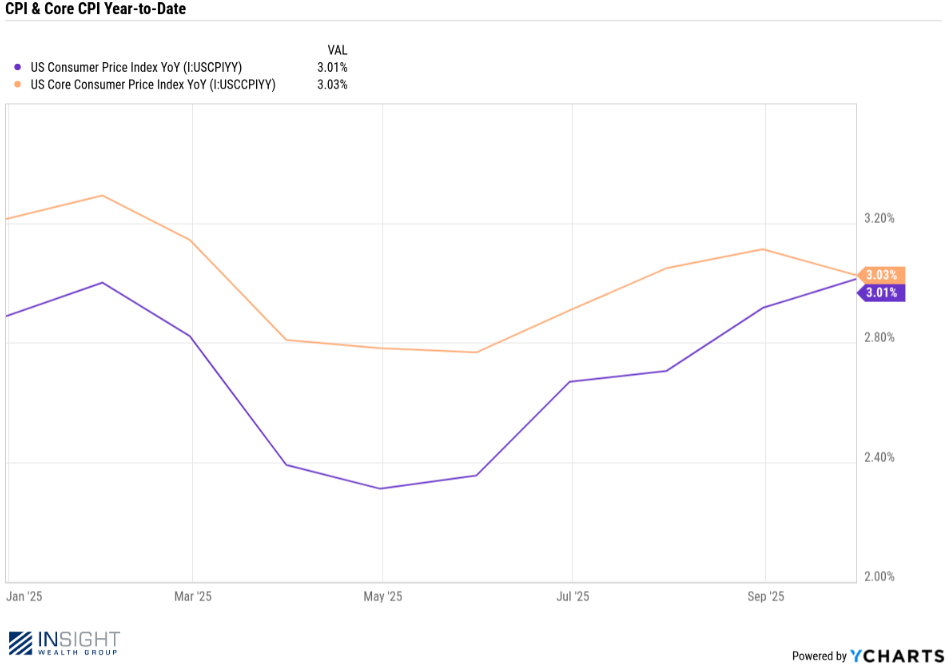

Which brings us to the Fed’s other mandate: keep inflation down. Much like the jobs discussion the data on inflation is okay, but not great. But unlike jobs, we have recent data. The CPI data dropped last week, and it was nothing remarkable. Both Core and All-Items CPI came in right at 3%. That’s higher than the Fed would like, but not problematic.

Past performance is not indicative of future results.

The Tariff Question

If the jobs data and the inflation data are both unremarkable and remain that way, one could make a convincing argument that the Fed is not motivated to continue cutting rates. That alone would make the market’s prognostication for the future overly optimistic.

But what, if anything, could move either of these numbers? On the jobs front, we don’t see much driving further layoffs at the moment. Companies are too profitable, and the government is spending too much money, to drive significant unemployment.

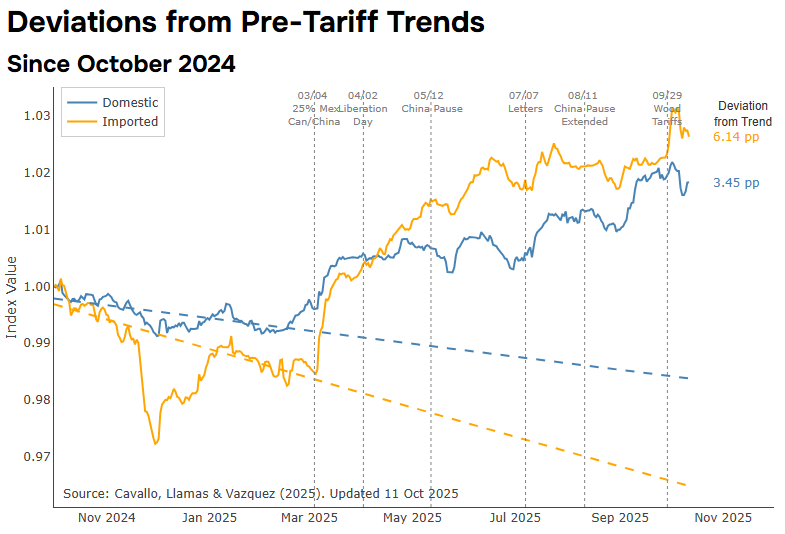

It is the inflation side of the picture that offers the most risk. And that risk is tied directly to the costs associated with tariffs. We know that tariffs increase prices, and we’ve seen that – to a limited degree – so far. Interestingly, it impacts domestic goods nearly as much as it does imported goods!

Source: www.PricingLab.org

Past performance is not indicative of future results.

But these price increases haven’t been enough to cause inflation to really spike. Is it more than ideal? Yes. But it’s not catastrophic.

But there’s one part of this process that hasn’t bitten inflation yet: most of the tariffs are being paid by corporations instead of consumers. Per Goldman Sachs, 37 percent of tariffs were borne by consumers through August. The remaining costs were being “eaten” by companies and their foreign suppliers (51% companies, 9% suppliers).

Why? It’s not the kindheartedness of corporations! Instead, they’ve been dealing with the uncertainty surrounding tariffs (and a hope they might go away) and exceptionally good profit margins. That’s given them the ability to wait it out.

General Motors is a fitting example. They announced in their recent earnings report that the company anticipated paying $3.5 – $4.5 billion in tariffs this year. Yet they have only raised their prices by one percent this year. That decision has significantly impacted their margins, which have fallen from 9% to 6.2% so far this year.

That can’t – and won’t – continue forever. Companies are accountable to their investors. And investors want returns, not charity for consumers. If the tariff regime continues, prices will rise more for consumers.

The good news is, as Chairman Powell has stated, tariff inflation is a “one-time hit” to the inflation numbers. Any increase in prices will not repeat every year. But inflation can have wide-ranging impacts on the economy even if it is short-term.

So where does that leave us? There is little question we’ll get a rate cut this week. But we’d also argue the weight of the evidence points to rate cuts slowing or stopping in the mid-term. We’d suspect the Fed sees little benefit to continuing cuts compared to the risk of rising inflation.

The market won’t like that message – especially if Powell delivers it on Wednesday. So don’t be surprised if a rate cut – the thing the market wants – is received by markets going down when Powell steps to the podium on Wednesday.

Sincerely,